Potential spring movements by hoary bats (https://www.fort.usgs.gov/science-feature/114)

Overview

Not all bats spend winter hibernating in caves. Some species migrate hundreds or thousands of miles across North America to avoid low temperatures and lack of food during winter.

Identifying important habitats and migratory routes for bats is required to know when to curtail and where to place wind turbines to minimize bat mortalities.

Project Blog

Project Description

Through the deployment of ultrasonic acoustic detectors for four years, we plan to document phenology of bat activity and timing of bat migration in eastern Nebraska. Furthermore, we hope to be able to determine if bats are using landscape features such as rivers as navigation corridors or if a broad front migration is occurring. As the project develops, we hope to use additional techniques to identify precise movements, residence time, and origin of bats migrating through Nebraska.

Project Importance

Bats are currently faced with two challenges, wind energy and white-nose syndrome. Knowing more about migration may be important to help minimize impacts of both of these challenges to bats.

Wind Energy & Bats

- Wind energy kills an estimated 600,000-800,000 bats a year across the United States.

- Most of the species killed are migratory, moving hundreds to thousands of kilometers between maternity and wintering grounds each year.

- It is during this period of movement (especially the fall) that the greatest mortality at wind farms has been observed.

- Unfortunately, knowledge about bat migratory movements is extremely lacking, and limits our ability to avoid or mitigate impacts to bat populations.

- With the current push for renewable energy in the United States (and world-wide) knowledge about bat migratory behavior is invaluable.

Dead bat at wind energy faciility

Echolocation

Basics of Echolocation

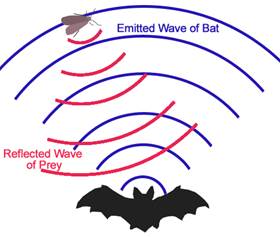

Echolocation is a natural sonar used by bats and dolphins to navigate and capture prey items. The animal produces a sound wave that then reflects off other surfaces. By listening for the echo, bats can then determine distance, orientation, speed, and size of objects.

This powerful sound is emitted from the bats vocal cords, often timed with wing beats in order to reduce the high amounts of energy required for producing ultrasonic pulses.

Echolocation is high frequency sound in the range of about 6 to 300 kilohertz (khz), well above typical human voice is range of 0.085 to 0.255 khz. Humans can hear up to approximately 20 khz, although the high end of this range is often lost as we age.

In Nebraska, most bats echolocate between 20 and 200 khz, so you may occasionally hear the lower end of 1-2 species as clicks above you; however most bats will be silent to you.

For more information on echolocation, how it was discovered, and its uses, please read:

- Seeing in the Dark (Bat Conservation International)

- How do bats echolocate and how are they adapted to this activity? (Scientific American)

Using Echolocation to Study Bats

We are able to record the sounds bats make using ultrasonic microphones and digital sound cards. This is a much easier, efficient, and accurate process than historical methods used to reduce sound to levels that we can hear (Frequency Division and Time-Expansion).

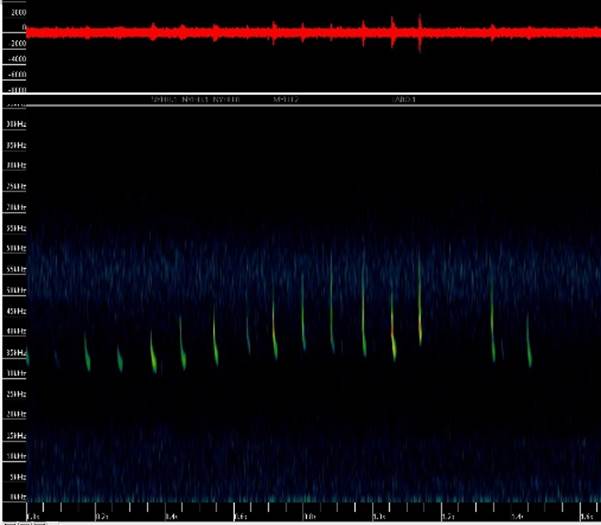

Once the sound is recorded, we can view the recordings on the computer.

We compare the shape and frequency of the calls collected to recordings from bats that were captured. This comparison can be done visually by a person or by using software that uses dozens of parameters to assign each call sequence to a species (like voice recognition).

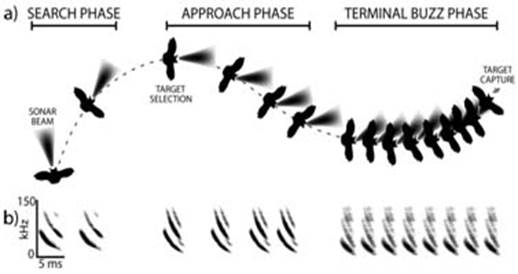

As a bat approaches its insect prey (a) it increases the frequency the its echolocation pulses, (b) We classify the signal into a search, approach, and feeding (terminal) buzz phase

Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis). Image by Keith Geluso.

Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus).

Spectrogram and audio (played at 1/8 of speed) of an Eastern red bat (top) and hoary bat (bottom). Notice the higher frequency, steeper slope, increased frequency range (70-30 khz) and shorter duration of the eastern red bat call.

Project Blog

Ever wonder what it is like to be a bat ecologist? How do you set up an ultrasonic acoustic detector?

Project updates will be provided here so you can learn more about these and other questions. For the complete update, click on the date of the blog entry.

January 2016

The ultrasonic acoustic detectors were deployed from April - Novemeber 2015. Big brown bats and eastern red bats were the most recoded bat species.

In 2015, bat calls were recorded for 42,939 detector hours during 239 calendar days. Current analysis indicates a total of 3,822 detector nights and more than 580,000 bat call sequences were recorded.

Some of the study sites have much more bat activity than others. What landscape, weather, or other elements are influencing the activity patterns will be explored this winter.

March 2015

During the winter months, work focused on identifying sites and testing and preparing equipment for deployment of all detectors by April, 2015.

Replacement parts for the ultrasonic acoustic detectors were ordered and received. New mounts were designed to better withstand Nebraska's strong winds and other inclement weather.

Permission to deploy detectors at a number of new sites was gained and complete coverage across the sampling grid is anticipated by deployment time.

December 2014

Data was collected through the week of November 24th, when the first prolonged cold snap hit Nebraska. Most of the detectors were removed for winter in order to make sure they are not damaged by freezing conditions. This year we have a total of 952 detector nights and have recorded 104,989 bat sequences.

Visual inspection of the time series is already allowing us to discern patterns in bat activity. Correlating these with landscape and weather patterns will allow us to better understand migration patterns. Not surprisingly, very little bat activity was seen after September.

During the months of November and December, much work has been focused on identifying sites and testing and preparing equipment for deployment of all detectors by April, 2015.

Ocotber 2014

The project has rapidly been developing and we were able to get a good pilot test of our study design and refine our equipment set-up this fall. We now have 11 bat detectors continuously gathering data and will add another 10 this spring. Data is collecting so rapidly I have trouble keeping up with it!

This quarter, we finalized our initial study design to consist of a 25 km grid of detectors (Figure 1). Combining this with last quarter's test of height, we began looking for appropriate areas to place detectors in our study design. We targeted areas to test difference in bat activity along rivers and within the general landscape, as well as discerning North/South vs East/West movement.

We were able to establish 7 additional detector locations before fall migration. Two of these are located on public land (Desoto NWR and Fremont lakes SRA) while the other 5 are on private land. We have had excellent public support in access grain elevators and silos in order to elevate our detectors to the required 50+ feet.

This year we have a total of 952 detector nights and have recorded 104,989 bat sequences. Visual inspection of the time series (Figure 2) is already allowing us to discern patterns in bat activity. Correlating these with landscape and weather patterns will allow us to better understand migration patterns.

Work will continue into November based upon weather. Most (if not all) detectors will be removed for winter in order to make sure they are not damaged by freezing conditions.

July 2014

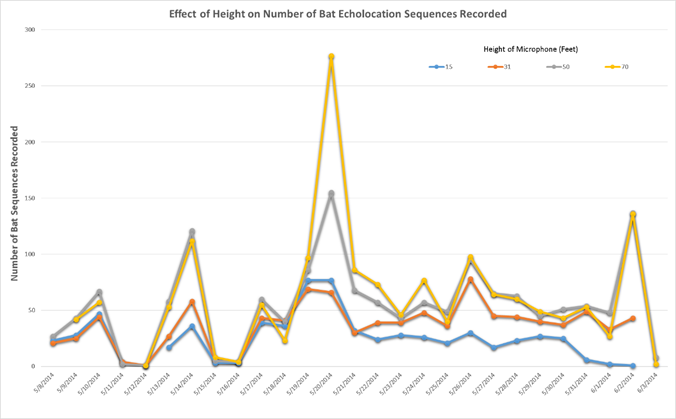

The spring migratory period will be dedicated to testing equipment and establishing protocols. One of the most important things to determine is how high our microphones should be placed. Higher is thought to be better, but there is very little on how high is high enough. We set out to determine that.

It has been a busy spring and summer (can't believe its almost over!). In April and May we placed 6 detectors at 4 locations to examine height and setting requirements (and to just get used to the new equipment).

We have been pleasantly surprised at how long our batteries last (over one month!), requiring less driving around and more time for other studies.

The current data is showing us that we need to target locations 50-75 feet in height (see graph below). To do this we are targeting silos and grain elevators in a grid across centered along the Platte river in the eastern portion of the state. While there are probably tens of thousands of these structures in this part of the state, finding ones where we need them is sometimes difficult (especially along the rivers). While it has been slow finding additional sites to place detectors, we have come up with a study design and plan and hope to have 10 detectors up by August. The cooperation of private landowners has been phenomenal and will be integral to the success of the project.

Example bat echolocation call sequence collected along the Platte River.

Graph of number of bat echolocation sequences recorded at various heights, the larger peaks with higher microphones are likely migratory bats moving through the area in mid to late May

April 2014: Project Kickoff!

We are excited to kickoff our project this month! This spring we are placing bat detectors at locations along the eastern Platte River. You may notice some of our signs! We are also looking for towers 30+ feet along the Platte and surrounding areas to place bat detectors on. If you own a tower, please contact us at windwildlife@unl.edu or (402)472-8188.

The spring is finally upon us and we are working hard to place bat detectors along the Eastern Platte River. I have to say that the late spring is a blessing for me. I have been frantically trying to get the project ready since I started in January and the extra month of cold weather has likely delayed migration season and given me more time to prepare.

The spring is finally upon us and we are working hard to place bat detectors along the Eastern Platte River. I have to say that the late spring is a blessing for me. I have been frantically trying to get the project ready since I started in January and the extra month of cold weather has likely delayed migration season and given me more time to prepare.

Throughout the spring summer and fall, we will focus on testing equipment setup. We are particularly interested in seeing the differences in detection at various microphone heights.

We have been able to secure 5 detector towers and will place 7 detectors out by May. You may notice some of our signs marking detectors on public land. Please do not disturb the detector, microphone, or cable. If you notice anything wrong, please report it to the park staff and they will notify researchers. Microphones only record bat calls, and cannot detect sound below 16khz. Typical human voice is well below 1 khz, so your conversations are safe!

We have been able to secure 5 detector towers and will place 7 detectors out by May. You may notice some of our signs marking detectors on public land. Please do not disturb the detector, microphone, or cable. If you notice anything wrong, please report it to the park staff and they will notify researchers. Microphones only record bat calls, and cannot detect sound below 16khz. Typical human voice is well below 1 khz, so your conversations are safe!

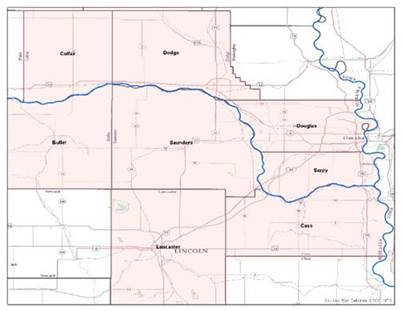

We are looking for more towers to place our detectors on. Anything 25 feet or over can be used: TV antennae, Ham radio masts, old windmills, feed elevators, anything tall! Towers within 1/4 mi of the Platte and Missouri Rivers in Colfax, Butler, Dodge, Saunders, Douglas, Sarpy, and Cass counties are of particular interest. However, any tower in those and Lancaster County could be beneficial to the study. Please contact us if you own a tower and would be willing to hear more about placing a bat detector on it.

Findings

Findings will be reported once data collection and analysis has occured. Check back.

Partners

The Nebraska Bat Migration Initiative is an effort of the Nebraska Wind Energy and Wildlife Project within the Nebraska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

Generous funding is provided through a grant from the Nebraska Environmental Trust and the Nebraska Game and Parks Commision's Wildlife Conservation Fund.